They began about 34 million years ago as balloons of hot magma rising into the surrounding limestone. Over time, the overlying limestone eroded away, exposing the more resilient granite domes beneath.

The cave walls of what is now Hueco Tanks State Park & Historic Site have been a canvas for generations of primitive people to tell their stories – the cracks and crevices a foothold for modern climbing enthusiasts.

Atop the park’s three mountains, wind and rain have scooped out rounded hollows in the rock – known as “huecos”. Water collects in these pools and supports a thriving ecosystem of grasses, shrubs and trees in what resembles a lush rooftop garden. Under the shade of a rock overhang, a patch of ferns clings to life in what is otherwise a dry Chihuahuan desert.Look closely, and there’s life even in the ephemeral pools. Tiny orange fairy shrimp swim in schools across their sandy bottoms. Their eggs survive when the pools dry up, hatching again with the next rain. Many of the thousands of huecos here are dry, but some hold water for months at at time.

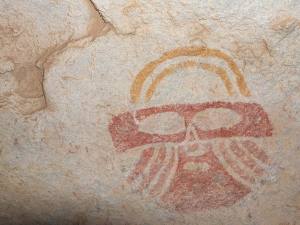

Beginning more than 10,000 years ago, primitive hunter-gatherers passed through Hueco Tanks, recording some of their hunts in simple art on the nearby rock walls. With the emergence of agriculture, the Jornada Mogollon followed about 1,000 years ago, building homes and cultivating corn and beans. Shards of their pottery and tools still lay along the park’s trails, and their colorful pictograph masks are scattered throughout the park. More recently, the Kiowa, Mescalero Apache and Tigua indians added their own stories and myths to the rock.

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t end there. Over the years, hundreds of visitors to Hueco Tanks have made their own mark – adding names, dates and drawings that in some cases have obliterated the primitive rock art. In the early 1990s, the park got a reputation as a world class climbing destination, pushing its annual visitors over 100,000.

To protect the primitive art and the rocks themselves, Hueco Tanks now limits the number of visitors daily and closes off most of the park to the general public. To climb or explore the rocks of North Mountain, you have to have a daily permit. East and West Mountains are off limits, except for limited tours Wednesdays through Sundays. Some permits can be reserved in advance, and a handful of others are held for release each day.Casual climbing requires some concentration but is not overly difficult, unless you want it to be. And apparently some people do. On a recent visit, a handful of climbers scoured the mountaintop for the most challenging paths.

The “trails” on the mountain are fairly indistinct. Once you get into the rocks the path is often obvious from where the rock is worn smooth. On top, you can wander at will.

Several trails are wedged among the rocks. The Chain Trail climbs up over North Mountain and provides a handhold much of the way. The Site #17 Trail is a good path to the rooftop garden and its collection of huecos. The rocks have a lot of footholds, which take you up past a wall of graffiti, through a gateway in the rocks that conceals a small pond before emerging on top.

Another trail wanders through the mesquite and creosote to Mescalero Canyon, but public access stops short of a small dam and its associated pond. All three trails have some rock art along the way, though it is severely faded in places.

A longer trail parallels a gravel park road, passes a large pond and curls around the north side of North Mountain.

Next to the visitors’ center, where you’re required to watch a short conservation movie, there’s a wall of relatively simple drawings and a short trail that winds around a picturesque pond.

The most striking publicly available rock art is on the roof of Cave Kiva on North Mountain. You’ll need detailed directions from the visitor’s center to get there and have to shimmy on your back to slip inside.

Once inside, just lay back and take in eight different masks from the Jornada Mogollon that are painted in bright reds and yellows on the rock above.