I thought, what if everyone could report their sightings in one place? What if I could go there to discover not only what birders were seeing right now but when the Bonaparte’s Gull tends to arrive at Bolivar Flats each winter?

It turns our there are just two simple steps in making it happen. First, think of something like this that would be incredibly useful. Second, do a Google search.

That’s how I came across eBird, part of the amazing suite of bird resources assembled by the Ornithology Lab at Cornell University. Thousands of birders and birding groups across the country report millions of sightings there every month.

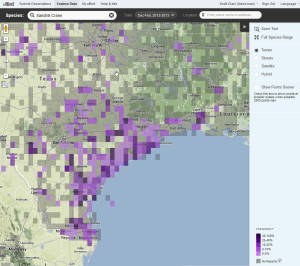

Those sightings can be sorted by date and location or combined to produce interactive range maps that track trends over the years. And in some areas of the site, you can drill down to the underlying checklists turned in by individual birders, such as this one who recently photographed a Mexican Jay on Big Bend National Park’s Lost Mine Trail.

Although it launched in 2002, the site has extended its reach back more than 100 years by incorporating historical archives from a variety of sources. For example, on Saturday, Nov. 26, 1904, a sighting of two Ivory-billed Woodpeckers was reported in Tarkington Prairie, Texas, just east of Cleveland. (The last sighting in the eBird database of that now presumably extinct bird was reported on May 12, 1935 in the Santee River Swamp of South Carolina.)

Individual birders can create new checklists on the site as well as import their existing records. They are then available to be shared with other birders or assembled into various personal reports. Birders can sign up for alerts about rare birds, or get notified when any bird not already on one of their checklists is sighted in their area.

All of this comes together to create a broad picture of bird activity across the country – and the world.

How do we know that all these people really saw what they thought they saw? eBird explains:

Using advanced data vetting technology, we’ve developed a combination of automated filters and a network of regional editors that work together to verify eBird data. Each eBird submission, regardless of observer or location, is checked for data quality in exactly the same way…. Being questioned about a record is not personal. It is simply a request for more information so that your record will hold up to scientific scrutiny.

Presumably rare bird sightings get particular scrutiny while lesser errors are overwhelmed by the mass of the data.

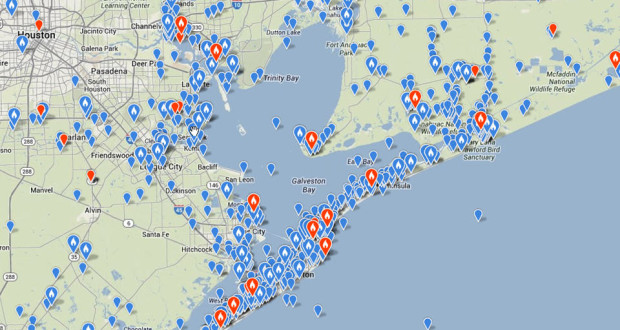

A section of the site focuses just on Texas. Here are birding charts for several nearby “hot spots”:

- Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge

- Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge

- Bolivar Flats

- Boy Scout Woods Sanctuary

- Brazoria National Wildlife Refuge

- Brazos Bend State Park

- Galveston Island State Park

- McFaddin National Wildlife Refuge

- Sabine Woods Sanctuary

- San Bernard National Wildlife Refuge

By the way, the Bonaparte’s Gull arrives on Bolivar Flats in December and is usually gone again by late March, according to sightings over the last 10 years.